Ah, we meet again, my old friend.

After recently joining Splunk, I got to experience a bit of an old nemesis of mine after being bombarded by firehoses of new data and information. It’s been a while since I felt it, but it’s no less awful than I remember.

Over the years, I’ve learned how to re-orient my thinking when that feeling appears. This article describes how I deal with it and some techniques that might be helpful to you.

A big head

When it comes to being intelligent, you can always bet on one thing…

There is always someone else more intelligent than you.

I didn’t know this early on in my career. I had an ego the size of a house, and my internal position was generally:

I’m so bright; you all need sunglasses to look at me.

My ego was smashed to bits a good few times, and after having my ass handed to me multiple times, I eventually learned.

I finally understood.

Humility is not weakness.

It’s strength.

The fear

At some point, we all find ourselves in a position where it seems that everyone around us is somehow much more intelligent than we are.

It can feel like punching way above our own weight as if we’re out of our depth.

The syndrome can be summarized as:

A fear that more competent people will suddenly discover that we’re not as bright as they thought.

Imposter syndrome attributes that we have only been successful because we got lucky.

It also manifests as the feeling of having deceived others into thinking we’re more intelligent or skillful than we really are.

This is despite evidence to the contrary.

It’s OK.

First of all… if you feel this way - I want you to know that you’re normal.

The fact that you’re able to feel inadequacy demonstrates humility. Humility is a crucial component of emotional intelligence, also known as EQ.

Emotional intelligence and developing it will be critical to level up into those higher career ranks. It’s essential to become a better leader, influencer, or just a better friend.

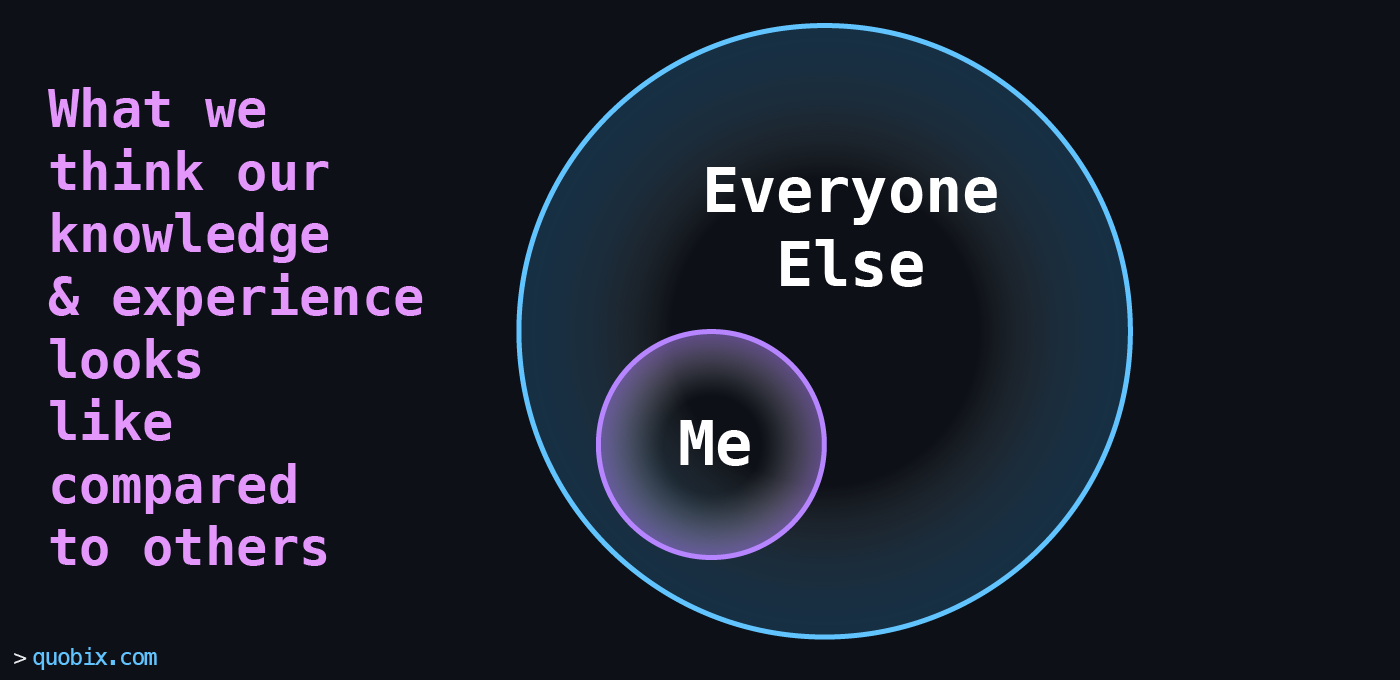

An excellent way to visualize imposter syndrome is to imagine knowledge and the knowledge of others around us as spheres.

Spheres of knowledge

When we’re new to a company or a team in an unfamiliar domain, we tend to imagine everyone around us with these giant bubbles of knowledge around them, and our bubble is puny and unworthy.

The fear another will ‘discover’ that we’re not as competent as we should - can be intense.

Simply being asked to contribute can almost drive us to avoid interaction with others, shying away from answering questions or even participating in projects.

The fear of being seen as inferior can be challenging to overcome.

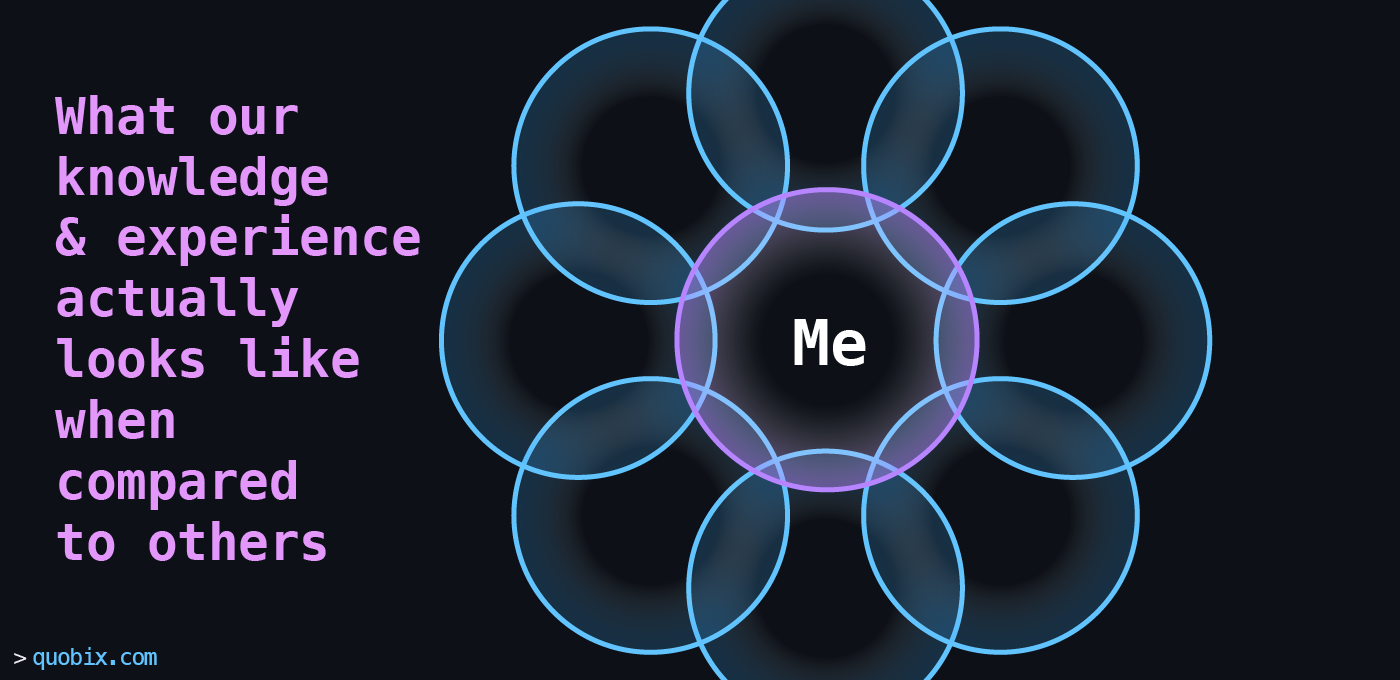

The reality is that everyone around us has bubbles of knowledge that overlap with ours; they know things we don’t and vice versa, like a Venn Diagram.

We all overlap

They may have super-specialized knowledge about a set of technologies that we have a very light comprehension of. Still, they may know nothing about the technologies and techniques we do. We may have skills they don’t.

Apples to oranges

We cannot compare ourselves to our peers. Even though two people may be colleagues, at the same level, they are not equal.

Everyone’s skills and experiences are different, which means we hold knowledge in many other areas from one another.

When we combine diverse knowledge, amazing things happen.

When we accept different people bring different values to the table, the importance of diversity and inclusivity become clear.

A few steps away from having no idea

It’s easy to forget the depth and breadth of our own skills and experience when being impressed by what others bring to the table.

Everyone around us is mostly figuring things out as they go along; rarely does anyone have the detailed knowledge required to handle a new situation.

Everyone is generally just a few steps from having no idea what to do.

Almost everyone is affected, from interns to the most seasoned CEOs.

When a senior leader says “I don’t know,” it’s not them declaring weakness; it is, in fact, an invitation for others to step up and contribute knowledge to the community.

Saying “I don’t know” is how we all become more experienced, wiser, and more valuable.

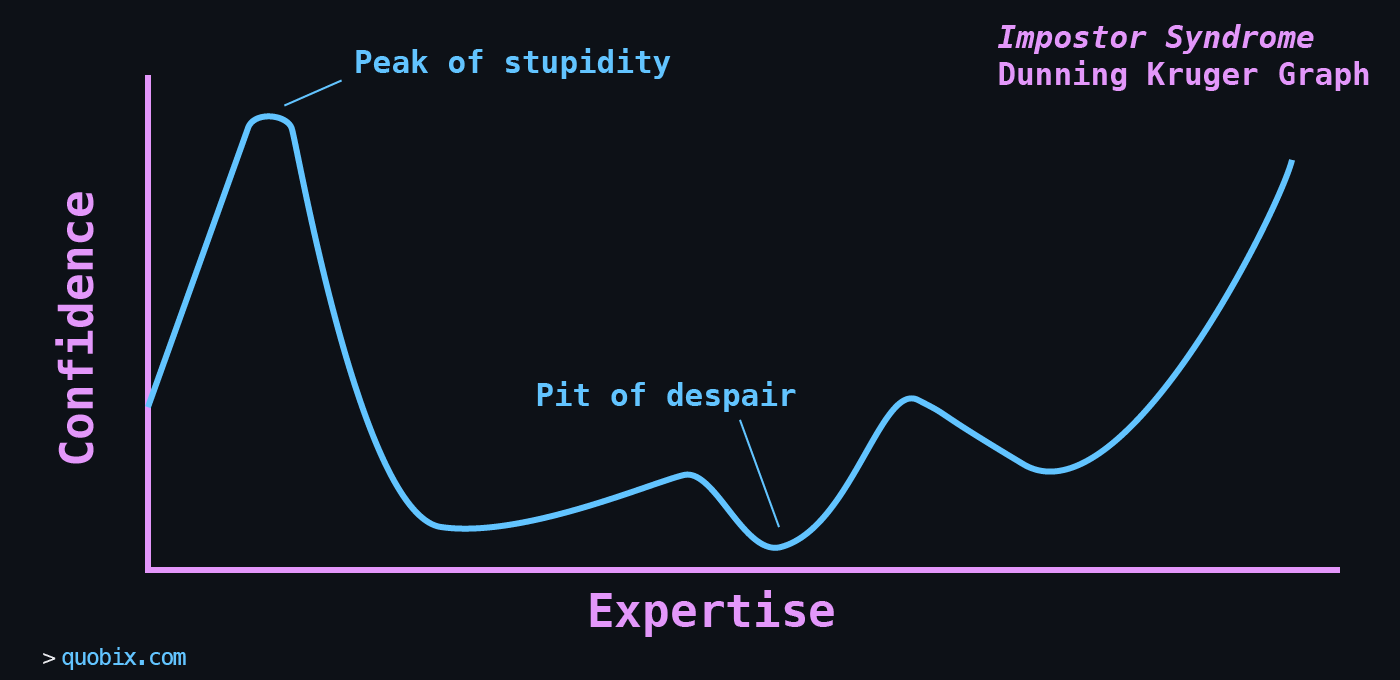

The Dunning Kruger graph

I used to suffer from this syndrome a lot. I went through the Dunning Kruger Graph multiple times.

Dunning Kruger hypothesizes that people with low experience in a domain often overestimate their skills and ability. Often with high confidence, it’s a good illustration of the idea of illusory superiority.

During the pandemic, people with no medical or scientific training suddenly became ‘experts’ in immunology. This is a perfect example of the concept.

I never went to college, so I taught myself computer science and software engineering.

I always felt like I was much less knowledgeable when talking to other engineers early on.

My constant ‘flight’ or ‘fight’ reflex engaged, so I don’t make a fool of myself, has caused me to ruin the armpits of many a shirt over the years.

Yeah, I got this - oh, no, wait…

The Dunning Kruger theory states that confidence rapidly rises as we learn a new set of skills. However, it can only grow so much before reaching the peak of stupidity.

Once a certain amount of expertise has been gained, the reality is that we actually know very little about what it is we think we know. This is also generally the point where we can overly estimate our capabilities.

When we plow on and learn more about something and become more proficient in the art of it, our confidence starts to drop. The drop varies in steepness, depending on how high up on mount stupid we are.

For me, this is when impostor syndrome kicked in the hardest. I used to feel like I was half good at something, that I was actually a fraud compared to others.

Unfortunately, this feeling generally got worse as I learned more. Which resulted in feeling even more, fraudulent.

Bottoming out

After a while in the pit of despair, something starts to happen.

Patterns begin to appear. Problems we have seen before and know how to solve.

This starts to reverse the trend, and confidence begins to rise quickly again. Becoming fluent in those patterns and eventually becoming an expert.

If we feel like an impostor, it generally means that we’re smart enough to have gone past the peak of stupidity. We have slid down the other side and realized the true scope and scale of the art.

To beat this feeling? Just keep going.

Treating failure as another form of education.

Experience is essentially having made enough mistakes to know how to fail at something. Edison said:

I didn’t fail; I just found 2000 ways not to make a light bulb.

Applying experience is how we become successful in not failing.

Feeling like an impostor is just a reminder that you’re on the right path and there is more to learn.

So just keep going. Keep training, keep learning, keep practicing.